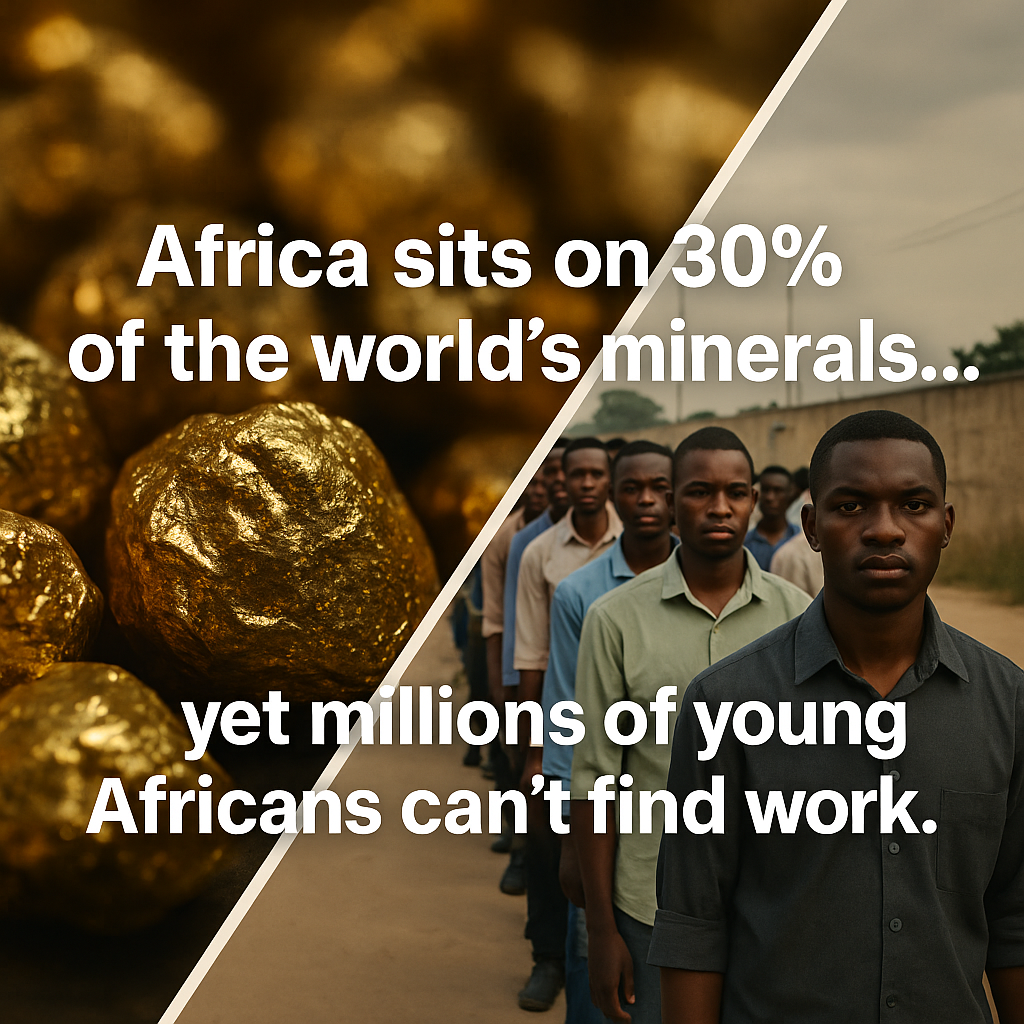

Africa’s mineral paradox

Africa holds about 30 % of the world’s known mineral reserves but attracts less than 10 % of global exploration spending—a telling mismatch between geological promise and realised value.(Mining Indaba, Africa Center) While copper, cobalt, lithium, iron ore and gold lie beneath vast tracts of land, the benefits rarely flow to the continent’s 1.4 billion people.

1. Foreign hands on African ore

European investors still own the largest share of accumulated mining assets on the continent—$60 billion from the UK, $54 billion from France and $54 billion from the Netherlands—while Asian, Gulf and Australian groups race to catch up.(IMF)

- Canada’s Barrick Gold is fighting Mali’s military government over control of the Loulo-Gounkoto mine.(Reuters)

- UAE-based IRH snapped up 51 % of Zambia’s Mopani copper complex in 2023.(Financial Times)

- BHP has just paid to earn up to 75 % of new copper licences in Botswana’s Kalahari Copper Belt.(news)

- Chinese firms already control an estimated 46 % of global cobalt supply through Congolese assets and are expanding rapidly in African lithium.(MINING.COM, MINING.COM)

These deals are structured so that technology, managerial posts and the bulk of profits stay offshore, leaving host governments reliant on taxes and royalties that are hard to audit.

2. A jobs crisis amid plenty

Large-scale mines are capital-intensive: they account for well under 1 % of Africa’s workforce, while agriculture and the informal sector absorb most labour. The International Labour Organization projects youth unemployment at 8.9 % for sub-Saharan Africa in 2024-25, but that headline masks severe under-employment; in South Africa, open unemployment reached 32.9 % in Q1 2025 and a staggering 43 % when discouraged job-seekers are included.(International Labour Organization, Reuters)

Without industrial linkages or local procurement rules that stick, mining enclaves often import everything from trucks to welders, leaving surrounding communities with security jobs or casual labour at best.

3. Rich seams that lie idle

The Simandou iron-ore range in Guinea—the world’s largest untapped high-grade deposit—has seen two decades of legal wrangling; production is now promised for 2025 – 28 but scepticism remains.(The Guardian) Nigeria lists 44 identified minerals, yet licensing bottlenecks and infrastructure gaps keep most of them in the ground.(Nigerian Mining) Across the continent, exploration spending trails the global average, leaving many proven prospects “stranded” until railways, power and ports materialise.

4. Old guards, young populations

Africa’s median age is about 20, but the median head-of-state age tops 60—the widest generational gap in the world.(Club of Rome) Long-serving leaders and senior civil services often view mining through a 20th-century lens (export the ore, collect a rent) rather than the value-addition strategies their youthful electorates demand. Only a handful of under-45 leaders—Burkina Faso’s Ibrahim Traoré (37) or Senegal’s Bassirou Diomaye Faye (44)—buck the trend and symbolise popular frustration with gerontocracy.(BBC, Voice of America)

5. Democracy—preferred but disappointing

Afrobarometer finds 64 % of Africans aged 18-35 still prefer democracy, yet they are more willing than their elders to tolerate military takeovers when elected governments “abuse power.”(Afrobarometer) That ambivalence echoes in the Sahel, where juntas from Mali to Niger are rewriting mining codes to seize bigger state stakes—moves that spook investors but reflect public anger over perceived foreign looting.(Financial Times)

6. Missed chances—and what could change

Opportunities on the table include:

| Potential lever | What it could unlock | Why it stalls now |

|---|---|---|

| Local-content and skills mandates | 3-4× job multipliers in services, engineering, fabrication | Enforcement weak; governments lack monitoring capacity |

| On-site processing (lithium hydroxide, refined copper, battery precursors) | Higher export value, industrial clusters | Power deficits, policy flip-flops |

| Regional infrastructure corridors (e.g., Lobito Atlantic Railway, African Green Minerals Corridor) | Connect land-locked deposits to ports, cut freight costs | Financing gaps, political risk |

| Transparent contract databases (EITI++, Africa Mining Legislation Atlas) | Public scrutiny, reduced corruption | Some states reluctant to publish deals |

| Youth equity or royalty funds | Direct citizen stake in mines, seed capital for SMEs | Legal frameworks missing; elite resistance |

The African Union’s “Africa Mining Vision” already sketches many of these reforms—linkages, beneficiation, shared infrastructure—but implementation lags.(African Union)

Take-aways

- Foreign dominance is not inevitable: renegotiated royalties and equity only help if paired with skills transfer, supplier development and domestic capital mobilisation.

- Job creation requires moving beyond raw-ore export into downstream processing, renewables-powered smelters and service hubs.

- Youthful populations demand a new social contract; without generational renewal in leadership and genuine transparency, coups or street protests will keep erupting.

- Idle deposits represent latent wealth—but only integrated infrastructure, rule-of-law certainty and consistent policy can turn that wealth into broad-based prosperity.

The continent does not lack resources or entrepreneurship; it lacks governance that makes those two meet in productive, inclusive ways.